INTRODUCTION

Chronic and excessive use of alcohol is one of the major causes of liver disease.

90% of daily heavy drinkers (>60 g alcohol/day) as well as binge drinkers have fatty liver but a smaller percentage (10-35%) of drinkers progress to alcoholic hepatitis which is a precursor for cirrhosis.

The long-term risk is 9 times higher in patients with alcoholic hepatitis compared to those with fatty liver alone.

Some population-based surveys have documented that men must drink 40 to 80 g of alcohol daily and women must drink 20 to 40 g daily for 10 to 12 years to achieve a significant risk of liver disease.

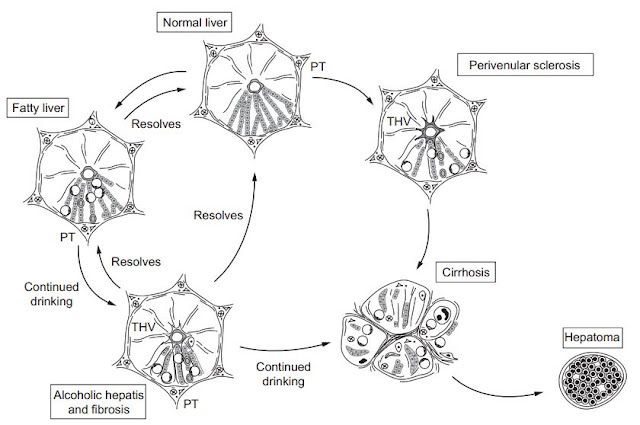

Liver pathology consists of 3 major lesions that are progressive and rarely exist in a pure form:

1) fatty liver (usually reverses quickly with abstinence),

2) alcoholic hepatitis and

3) cirrhosis.

Prognosis of severe alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is bad. Mortality of patients with alcoholic hepatitis concurrent with cirrhosis id nearly 60% at 4 years.

Although alcohol is a direct hepatotoxin, it is unclear why only 10-20% of alcoholics will develop alcoholic hepatitis. It appears to involve a complex interaction of facilitating factors like drinking patterns, diet, obesity and gender.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Harmful use of alcohol results in 2.5 million deaths each yr. Most of the mortality is due to cirrhosis. The mortality is declining now because of decreased consumption of alcohol in the Western countries except in the U.K, Romania, Russia and Hungary.

ETIOLOGY

a) Quantity and duration of alcohol intake - are the most important risk factors. Time taken to develop liver disease is directly related to the amount of alcohol consumed.

b) There is no clear role of the type of beverage and the pattern of drinking.

c) Genetic - some people are genetically predisposed for alcoholism and subsequently to the ill effects of alcohol on the liver.

d) Gender - It is a strong determinant for ALD. Women are more susceptible to alcoholic liver injury. They develop advanced liver disease with substantially less alcohol intake. Gender-dependent differences may be due to the effects of estrogen, proportion of body fat and gastric metabolism of alcohol.

e) Chronic infection with Hepatitis C virus - It is an important comorbidity in the progression of ALD to cirrhosis in chronic and excessive drinkers. Even moderate alcohol intake of 20-50 g/day increases the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer. Intake of more than 50 g/day decreases the efficacy of interferon-based antiviral therapy.

PATHOGENESIS

It is unclear but what is known is that alcohol can act as a direct hepatotxin and malnutrition does not play a major role.

- Alcohol is metabolised to acetyldehyde which in turn initiates an inflammatory cascade that results in a variety of metabolic responses.

- Steatosis from lipogenesis, fatty acid synthesis and depression of fatty acid oxidation occur secondary to effects on sterol regulatory transcription factor (SRTF) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha).

- Intestinal derived endotoxin initiates a pathogenic process through toll-like receptor-4 and TNF-alpha. This facilitates hepatocyte apoptosis and necrosis.

- Cell-injury endotoxin also activates innate and adaptive immunity pathways. There is release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha) and proliferation of T/B cells.

- Production of toxic protein-aldehyde adducts, generation of reducing equivalents and oxidative stress also contribute to liver injury.

Finally hepatocyte injury and impaired regeneration are associated with stellate cell activation and collagen production which are key events in fibrogenesis. The resulting fibrosis causes architectural derangement of the liver and the associated pathophysiology.

PATHOLOGY

Fatty liver is the initial and most common histologic response to hepatotoxic stimuli, including excess alcohol ingestion. Accumulation of fat within the perivenular hepatocytes coincides with the location of alcohol dehydrogenase. Continuing alcohol ingestion results in deposition of fat throughout the entire hepatic lobule.

Alcoholic fatty liver - traditionally regarded as benign but appearance of steatohepatitis and certain features like giant mitochondria, perivenular fibrosis and microvesicular fat are associated with progressive liver injury.

Hallmarks of alcoholic hepatitis include: (hepatocyte injury)

a) ballooning degeneration,

b) spotty necrosis,

c) polymorphonuclear infiltrate and

d) fibrosis in the perivenular and perisinusoidal space of Disse.

Mallory-Denk bodies are often present in florid cases but these are neither specific nor necessary to establish the diagnosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Usually the patients are asymptomatic.

Hepatomegaly is often the only clinical finding.

It is very important to assess the drinking history and estimate how much alcohol is consumed per day and for how long.

1 beer, 4-5 ounces of wine, 1.5 oz of 40% liquor and 1 ounce (approximately 30 mL) of 80% spirits all have around 12 g of alcohol.

- Patients with fatty liver may have:

1) right upper quadrant discomfort,

2) nausea and

3) rarely jaundice.

- Patients with alcoholic hepatitis may have:

1) fever

2) spider nevi

3) jaundice

4) abdominal pain.

We can also see portal hypertension, ascites and variceal bleeding even in the absence of cirrhosis.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

These are most identified through routine screening tests.

Fatty liver - laboratory abnormalities are non-specific

Modest elevation of AST, ALT, GGTP are seen. Triglycerides and bilirubin may also be increased.

Alcoholic hepatitis

a) increased AST and ALT - by 2-7 fold but rarely greater than 400 IU.

b) AST/ALT ratio greater than 1.

c) hyperbilirubinemia

d) modest increase in alkaline phosphatase

If synthetic function is deranged then the condition is more serious. Hypoalbuminemia and coagulopathy are more common in advanced liver disease.

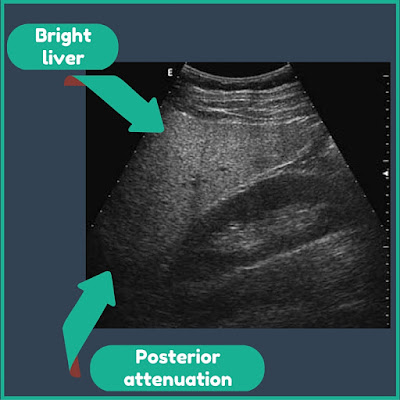

Ultrasonography is also a useful investigation as it can determine the size of the liver and detect any fatty infiltration. If it demonstrates portal vein flow reversal, ascites and intraabdominal venous collaterals then the condition has less potential for complete reversal.

Below is an ultrasonographic picture of hepatic steatosis. Fatty infiltration produces an increased reflectivity of hepatic parenchyma, known as ‘bright liver pattern’. This feature can be assessed by comparing liver parenchyma with the right kidney’s cortex, which normally presents an echogenicity equal to or slightly lower than that of the liver. Severe steatosis produces a strong attenuation in the deepest liver sections, resulting in poor explorability.

PROGNOSIS

Critically ill patients with alcoholic hepatatis have short term (30-day) mortality rates exceeding 50%.

A Discriminant Function (DF) above 32 and a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) greater than 21 is associated with poor prognosis.

Worse prognosis if there is associated:

a) ascites,

b) variceal hemorrhage,

c) deep encephalopathy and

d) hepatorenal syndrome.

TREATMENT

a) Complete abstinence from alcohol is the mainstay for treatment.

b) Patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis i.e. DF>32 and MELD>21 should be given Prednisone 40mg/day or Prednisolone 32mg/day for 4 weeks followed by tapering over 4 weeks.

c) Alternatively Pentoxifylline, a non-specific TNF inhibitor, can be used in a dosage of 400mg 3 times per day for 4 weeks.

d) Liver transplantation is an accepted indication for treatment in selected and motivated patients with end-stage cirrhosis.

Below is an algorithm showing how to manage alcoholic hepatitis:

N.B Monoclonal antibodies that neutralize serum TNF-alpha should not be used as studies have reported an increase in the number of deaths secondary to infections and renal failure.

First published on: 23 September 2015

Chronic and excessive use of alcohol is one of the major causes of liver disease.

90% of daily heavy drinkers (>60 g alcohol/day) as well as binge drinkers have fatty liver but a smaller percentage (10-35%) of drinkers progress to alcoholic hepatitis which is a precursor for cirrhosis.

The long-term risk is 9 times higher in patients with alcoholic hepatitis compared to those with fatty liver alone.

Some population-based surveys have documented that men must drink 40 to 80 g of alcohol daily and women must drink 20 to 40 g daily for 10 to 12 years to achieve a significant risk of liver disease.

Liver pathology consists of 3 major lesions that are progressive and rarely exist in a pure form:

1) fatty liver (usually reverses quickly with abstinence),

2) alcoholic hepatitis and

3) cirrhosis.

Prognosis of severe alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is bad. Mortality of patients with alcoholic hepatitis concurrent with cirrhosis id nearly 60% at 4 years.

Although alcohol is a direct hepatotoxin, it is unclear why only 10-20% of alcoholics will develop alcoholic hepatitis. It appears to involve a complex interaction of facilitating factors like drinking patterns, diet, obesity and gender.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Harmful use of alcohol results in 2.5 million deaths each yr. Most of the mortality is due to cirrhosis. The mortality is declining now because of decreased consumption of alcohol in the Western countries except in the U.K, Romania, Russia and Hungary.

ETIOLOGY

a) Quantity and duration of alcohol intake - are the most important risk factors. Time taken to develop liver disease is directly related to the amount of alcohol consumed.

b) There is no clear role of the type of beverage and the pattern of drinking.

c) Genetic - some people are genetically predisposed for alcoholism and subsequently to the ill effects of alcohol on the liver.

d) Gender - It is a strong determinant for ALD. Women are more susceptible to alcoholic liver injury. They develop advanced liver disease with substantially less alcohol intake. Gender-dependent differences may be due to the effects of estrogen, proportion of body fat and gastric metabolism of alcohol.

e) Chronic infection with Hepatitis C virus - It is an important comorbidity in the progression of ALD to cirrhosis in chronic and excessive drinkers. Even moderate alcohol intake of 20-50 g/day increases the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer. Intake of more than 50 g/day decreases the efficacy of interferon-based antiviral therapy.

PATHOGENESIS

It is unclear but what is known is that alcohol can act as a direct hepatotxin and malnutrition does not play a major role.

- Alcohol is metabolised to acetyldehyde which in turn initiates an inflammatory cascade that results in a variety of metabolic responses.

- Steatosis from lipogenesis, fatty acid synthesis and depression of fatty acid oxidation occur secondary to effects on sterol regulatory transcription factor (SRTF) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha).

- Intestinal derived endotoxin initiates a pathogenic process through toll-like receptor-4 and TNF-alpha. This facilitates hepatocyte apoptosis and necrosis.

- Cell-injury endotoxin also activates innate and adaptive immunity pathways. There is release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha) and proliferation of T/B cells.

- Production of toxic protein-aldehyde adducts, generation of reducing equivalents and oxidative stress also contribute to liver injury.

Finally hepatocyte injury and impaired regeneration are associated with stellate cell activation and collagen production which are key events in fibrogenesis. The resulting fibrosis causes architectural derangement of the liver and the associated pathophysiology.

PATHOLOGY

Fatty liver is the initial and most common histologic response to hepatotoxic stimuli, including excess alcohol ingestion. Accumulation of fat within the perivenular hepatocytes coincides with the location of alcohol dehydrogenase. Continuing alcohol ingestion results in deposition of fat throughout the entire hepatic lobule.

Alcoholic fatty liver - traditionally regarded as benign but appearance of steatohepatitis and certain features like giant mitochondria, perivenular fibrosis and microvesicular fat are associated with progressive liver injury.

Hallmarks of alcoholic hepatitis include: (hepatocyte injury)

a) ballooning degeneration,

b) spotty necrosis,

c) polymorphonuclear infiltrate and

d) fibrosis in the perivenular and perisinusoidal space of Disse.

Mallory-Denk bodies are often present in florid cases but these are neither specific nor necessary to establish the diagnosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Usually the patients are asymptomatic.

Hepatomegaly is often the only clinical finding.

It is very important to assess the drinking history and estimate how much alcohol is consumed per day and for how long.

1 beer, 4-5 ounces of wine, 1.5 oz of 40% liquor and 1 ounce (approximately 30 mL) of 80% spirits all have around 12 g of alcohol.

- Patients with fatty liver may have:

1) right upper quadrant discomfort,

2) nausea and

3) rarely jaundice.

- Patients with alcoholic hepatitis may have:

1) fever

2) spider nevi

3) jaundice

4) abdominal pain.

We can also see portal hypertension, ascites and variceal bleeding even in the absence of cirrhosis.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

These are most identified through routine screening tests.

Fatty liver - laboratory abnormalities are non-specific

Modest elevation of AST, ALT, GGTP are seen. Triglycerides and bilirubin may also be increased.

Alcoholic hepatitis

a) increased AST and ALT - by 2-7 fold but rarely greater than 400 IU.

b) AST/ALT ratio greater than 1.

c) hyperbilirubinemia

d) modest increase in alkaline phosphatase

If synthetic function is deranged then the condition is more serious. Hypoalbuminemia and coagulopathy are more common in advanced liver disease.

Ultrasonography is also a useful investigation as it can determine the size of the liver and detect any fatty infiltration. If it demonstrates portal vein flow reversal, ascites and intraabdominal venous collaterals then the condition has less potential for complete reversal.

Below is an ultrasonographic picture of hepatic steatosis. Fatty infiltration produces an increased reflectivity of hepatic parenchyma, known as ‘bright liver pattern’. This feature can be assessed by comparing liver parenchyma with the right kidney’s cortex, which normally presents an echogenicity equal to or slightly lower than that of the liver. Severe steatosis produces a strong attenuation in the deepest liver sections, resulting in poor explorability.

PROGNOSIS

Critically ill patients with alcoholic hepatatis have short term (30-day) mortality rates exceeding 50%.

A Discriminant Function (DF) above 32 and a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) greater than 21 is associated with poor prognosis.

Worse prognosis if there is associated:

a) ascites,

b) variceal hemorrhage,

c) deep encephalopathy and

d) hepatorenal syndrome.

TREATMENT

a) Complete abstinence from alcohol is the mainstay for treatment.

b) Patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis i.e. DF>32 and MELD>21 should be given Prednisone 40mg/day or Prednisolone 32mg/day for 4 weeks followed by tapering over 4 weeks.

c) Alternatively Pentoxifylline, a non-specific TNF inhibitor, can be used in a dosage of 400mg 3 times per day for 4 weeks.

d) Liver transplantation is an accepted indication for treatment in selected and motivated patients with end-stage cirrhosis.

Below is an algorithm showing how to manage alcoholic hepatitis:

N.B Monoclonal antibodies that neutralize serum TNF-alpha should not be used as studies have reported an increase in the number of deaths secondary to infections and renal failure.

First published on: 23 September 2015

Good ost.

ReplyDeleteNice post. Keep sharing such a useful post.

ReplyDeleteAcupuncture Doctors in Chennai